Spotlight Delaware is a community-powered, collaborative, nonprofit newsroom covering the First State. Learn more at spotlightdelaware.org).

Earlier this year, the state spent half a million dollars to pay off medical debts for nearly 18,000 residents. State leaders argued that costs were too high in the state, and patients had been unfairly burdened by often crippling medical debt.

But as taxpayers footed the bill, which would ultimately erase $50 million in unpaid medical debt, the state’s largest hospital system has often spent a fraction of its multi-billion-dollar budget to ease those medical bills for Delawareans in the first place.

ChristianaCare, Delaware’s largest nonprofit hospital system, has doubled its revenue in the last decade. But during that same timeframe, its investments in free and discounted care have remained largely flat.

The revelation, pulled from the nonprofit health care giant’s annual tax filings, comes as health care costs continue to rise in the state and ChristianaCare attempts to grow its footprint in the region and dismantle regulatory measures meant to lower costs for patients.

Nonprofit hospitals are required by the IRS to provide a “community benefit” to earn their tax-exempt status. Historically, that benefit came in the form of providing free or discounted services, sometimes called “charity care.”

But changes in recent decades to federal and state guidelines have allowed nonprofit hospitals to set charity care policies at their own discretion, removing any requirement of providing it to patients in order to receive a tax break.

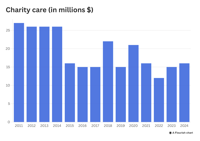

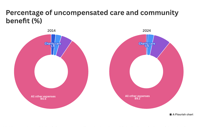

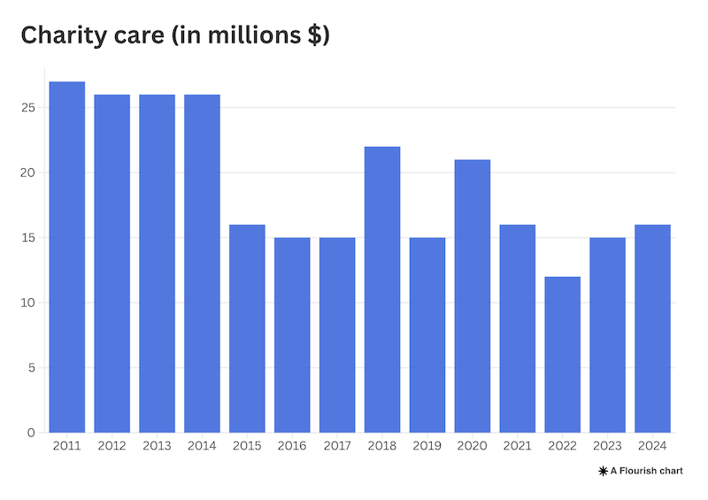

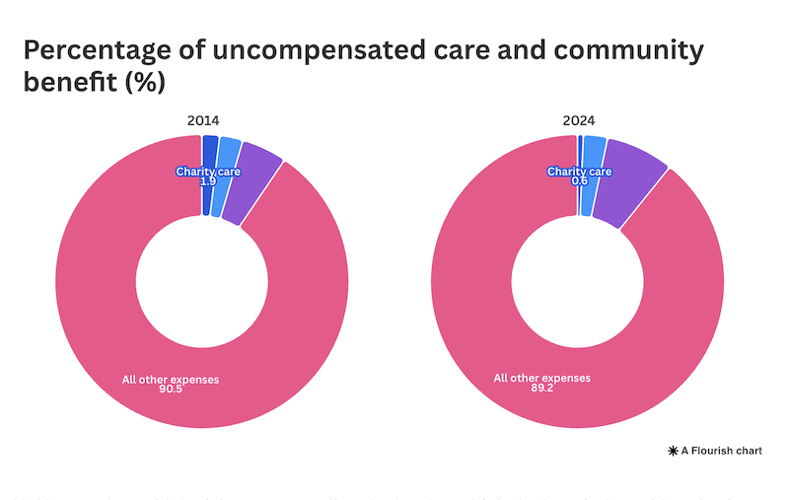

For ChristianaCare, this has translated to a steep decline in the percentage of free and discounted services provided to patients in the last decade. Charity care has made up less than 1% of the health care giant’s annual expenses since 2021.

In 2014, ChristianaCare spent $26.6 million providing free and discounted care – just less than 2% of its more than $1.3 billion in expenses – according to its tax filings. The IRS does not require hospitals to break down the amounts for each.

By 2024, that number dropped to $16.7 million.

The hospital system’s leadership maintains that charity care and service to the larger community are “fundamental” to its mission.

“I’m confident that we earn that tax-exempt status,” ChristianaCare Chief Financial Officer Rob McMurray said.

This stagnation in providing charity care coincides with ChristianaCare and other large, national health systems seeking to consolidate their market power across the country, something researchers have said could further stymie the amount of free and discounted services a hospital may provide.

“On one hand, they have deeper pockets, so they can do more of that,” Guy David, a professor of health care management at the University of Pennsylvania, said about an expanding hospital system’s ability to provide charity care. “On the other hand, they’re the only game in town. So, why should they?”

Maintaining nonprofit status

Before 1967, federal regulations surrounding charity care were “very clear” in that hospitals received their tax-exemption in exchange for providing relief for the poor, David said.

But following the creation of federal subsidies like Medicare and Medicaid, which were also meant to subsidize health costs, those regulations changed from offering relief for the poor to offering community benefits.

“Nobody knows what community benefits are,” David said.

With that change, providing free care to disadvantaged patients was no longer required. However, the IRS still considers it a “significant factor” in determining a hospital’s tax-free exemption.

According to the IRS, a community benefit could mean providing charity care, using surplus funds to improve facilities or spending money to increase access to medical training.

In Delaware, though, hospitals must provide charity care to patients living at or below 350% of the Federal Poverty Line.

In 2023, ChristianaCare raised its income eligibility to receive charity care from 200% to 400% of the Federal Poverty Line.

Charity care vs. community benefit

It is important to note that ChristianaCare and other hospitals do spend much more on their community benefits than solely charity care. However, as that total dollar amount for community benefits rises year over year, charity care has remained relatively flat.

In 2024, ChristianaCare spent more than $216 million on community benefits – about 8% of its total operating expenses and nearly $100 million more than the year prior.

But in that same year, spending on charity care rose by less than $1 million.

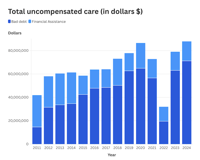

David, the Penn researcher, said that providing free care is not the only way to determine whether a hospital is charitable, and said there are two types of charity care. One, is a hospital providing care with no expectation of payment. The second, he said, is a provider’s “bad debt.”

Bad debt is when a hospital issues a bill to a patient hoping to get paid, but for one reason or another, that payment never comes. David said a key indicator of a hospital’s charitability is if that hospital decides to send that debt off to a collection agency, or simply write it off as a loss.

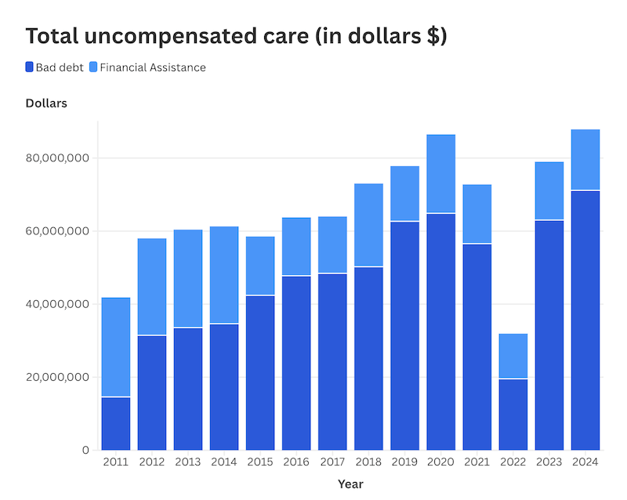

He said it’s important to look at all of the uncompensated care a hospital provides, which represents both of those figures

When looking at ChristianaCare’s bad debt combined with its charity care, the total amount the hospital system has spent annually since 2015 has gone up. While that dollar amount has gone up, the percentage against the hospital’s total expenses has decreased.

David also cautioned that an increase in dollars spent on uncompensated care does not always reflect an increase in the amount of care that was actually provided.

Using hospital data from California between 2001 and 2011, David and two other researchers found that while bad debt and charity care for hospitals dramatically rose over the years, the actual volume of treatment provided at a financial loss only slightly increased during that decade.

This, David said, reflects an increase in the price of hospital care.

ChristianaCare’s numbers

Last year, ChristianaCare ran a nearly $384 million budget surplus, more than triple the previous year. It also spent a fraction of a percent of its budget on providing charity care.

McMurray, the hospital’s chief financial officer, said in an interview with Spotlight Delaware that this year’s recent year spike in profit could be attributed to a strong year for investment income.

But surpluses for the hospital have been growing since 2015 and have averaged close to $210 million each year.

An additional examination of tax filings going back to 2011 shows charity care took a steep dip after 2014, and has since remained stagnant. In a statement to Spotlight Delaware, McMurray attributed this dip to a coinciding increase in Medicaid enrollment and expansion in Delaware.

McMurray also said decisions surrounding the level at which the hospital provides charity care is determined by its Board of Directors. He said the hospital does not set a budget amount for how much charity care it provides.

When it comes to determining who receives free or discounted care, he said patients are screened during admission to see if they qualify for the hospital’s charity care.

An examination of the hospital’s tax filings, however, show in some instances patients who qualified for financial assistance were billed. When asked about this, McMurray said those patients had been billed “inappropriately” and that once the hospital finds a patient is unable to pay, they clear the bills.

Hospitals have argued in the past that providing too much charity care ultimately brings up the price for paying patients as revenues decrease. But ChristianaCare already writes off tens of millions of dollars each year in bad debt, while revenues have exploded since 2015.

Additionally, prices at ChristianaCare and other Delaware hospitals are higher than most other providers in the nation, according to a recent presentation at a state board responsible for setting health care spending goals.

At a Delaware Economic and Financial Advisory Council meeting last month, a consultant hired by the state showed price statistics that placed ChristianaCare in the 87th percentile of inpatient stays nationwide.

McMurray did not comment on those figures in his statement and said the hospital is committed to delivering care at “affordable and transparent cost.”

When asked about the hospital’s financial assistance remaining relatively flat after it increased eligibility, he said that ChristianaCare’s threshold of 400% is “significantly above” other regional hospitals.

Additionally, he said the hospital “continues to assess” the level of financial assistance it provides to patients amid large federal subsidy cuts.

“We are actively engaged in planning for significant governmental funding cuts in Medicaid and Medicare funding and insurance coverage levels, which are happening at the same time we budget for projected expense growth due to workforce, pharmaceutical and supply chain inflation, and federally imposed tariffs,” McMurray said.

What others say

Ruth Landé, the vice president of provider relations at Undue Medical Debt, said there’s often a “communication gap” between patients and hospitals when it comes to charity care. She said in many cases, patients may not even know they are eligible for financial assistance, despite there being information on bills they receive.

“But if you ask a lot of patients, they’ll say they didn’t know about it,” Landé said. “Now, those patients are being absolutely truthful, and the hospital is being also truthful that they put it on every bill.”

She added the responsibility is not always on the hospital system, but also insurance companies that may not cover all procedures, leading to out-of-pocket payments.

Undue Medical Debt partnered with the state of Delaware earlier this year to pay off medical debt for close to 18,000 Delawareans using funds from the state’s General Fund.

Landé said she believes patients shouldn’t be getting bills for treatment, and instead, those payments should be settled between insurers and health systems.

“Take the patient out of it,” she said.

Ge Bai, a professor of accounting and health policy at Johns Hopkins University, said that most hospitals were in the past run by volunteers, and patients rarely paid for care.

What stemmed from that system, she said, was a change in the tax code – and an unspoken contract – where hospitals would be spared federal and local taxes in exchange for free care to lower-income members of the community.

But that idea is outdated and not representative of modern-day health care, Bai said. Now almost all patients pay for care in one way or another, whether through private or subsidized insurance.

In turn, she said that unspoken contract has become “obsolete,” as more hospitals begin to act like for-profit companies while still avoiding taxes.

“Every dollar spent on charity care is $1 less on their profit,” Bai said.

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.